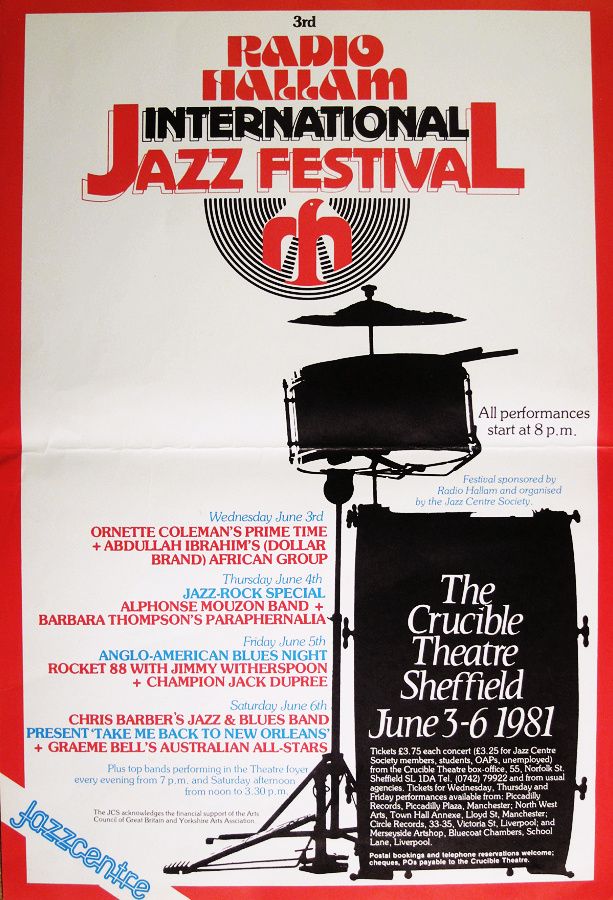

Concert poster courtesy of Steve Crocker.

To the best of my admittedly limited knowledge, Miles Davis never ran the voodoo down Fargate, not even in a silent way. John Coltrane never rolled his cool ‘trane into Sheffield Midland Station, preferring to express his love supreme elsewhere. So the news that Ornette Coleman, saxophone conquistador, musical philosopher and all-round jazz legend, is coming to our city is a very big deal indeed. To a jazz neophyte like myself - attracted initially by the sharp, retro stylings of Blue Note and Impulse! LP covers - this is a chance to learn from one of the acknowledged modern masters of the genre.

Coleman is bringing his six-piece band, Prime Time, to the Crucible Theatre as part of the Radio Hallam Sheffield Jazz Festival. Now in its third year the fest’s previous headliners have included last year’s Pharoah Sanders and, at its debut iteration, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

On the face of it, Radio Hallam, with its oatmeal mix of Shakin’ Stevens and REO Speedwagon, appears to be a strange bedfellow for a sonic explorer like Coleman. And while I’m still waiting to hear Johnny Moran slip a bit of ‘Ornette On Tenor’ into the breakfast show, it is good to know that behind the scenes there are passionate music fans keen to bring a diverse and unexpected range of sounds and styles to the airwaves and concert stages of South Yorkshire.

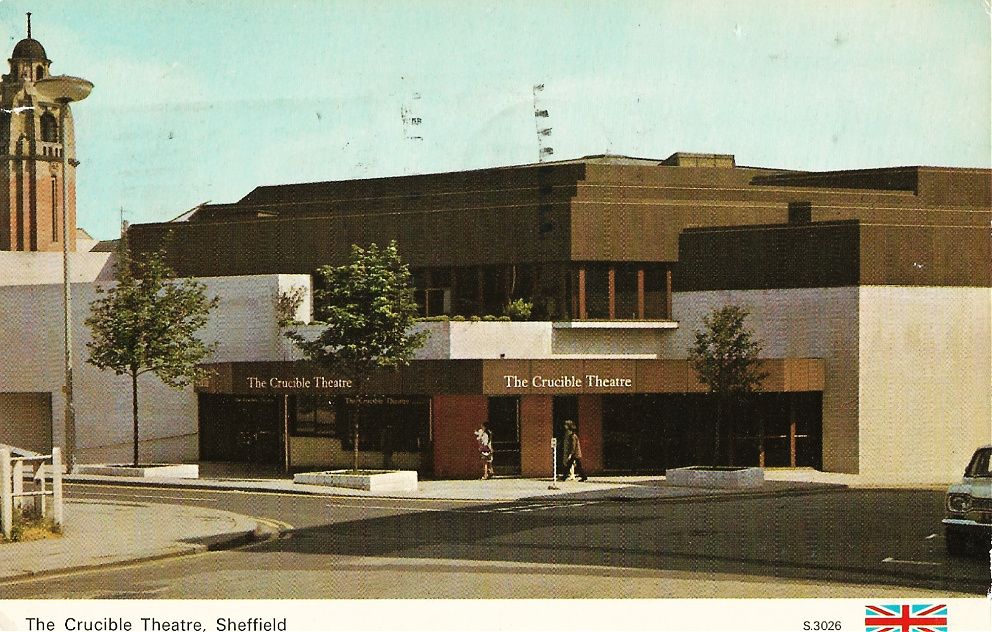

Tonight’s venue, the Crucible, is celebrating its tenth anniversary as the primo destination for Sheffield’s serious theatregoer. Brilliantly and accurately described by local writer Damon Fairclough as an “argument in concrete”, the Crucible is posh. Local folk with no interest in Shakespeare will pop in just to gawp at the carpet, hectares of russet, red and purple stretching like an irradiated Iowa as far as the eye can see.

Every year since 1977, this brutalist beauty overlooking Arundel Gate has transformed itself for three weeks in April into the world’s most-upmarket snooker hall - bringing in Pot Black fans of Ray Reardon and Eddie Charlton, who think Chekhov is a character in ‘Star Trek’.

We are out in force tonight. Me, Box-bandmates Charlie and Paul, Paul’s girlfriend Sue, plus Richard Kirk from the Cabs and his partner Lynn. We’re in the front-row, the semi-octagonal stage at our feet. Above us, hundreds of tiny lilly-lows - embedded in the ceiling - dim as Prime Time take to the stage.

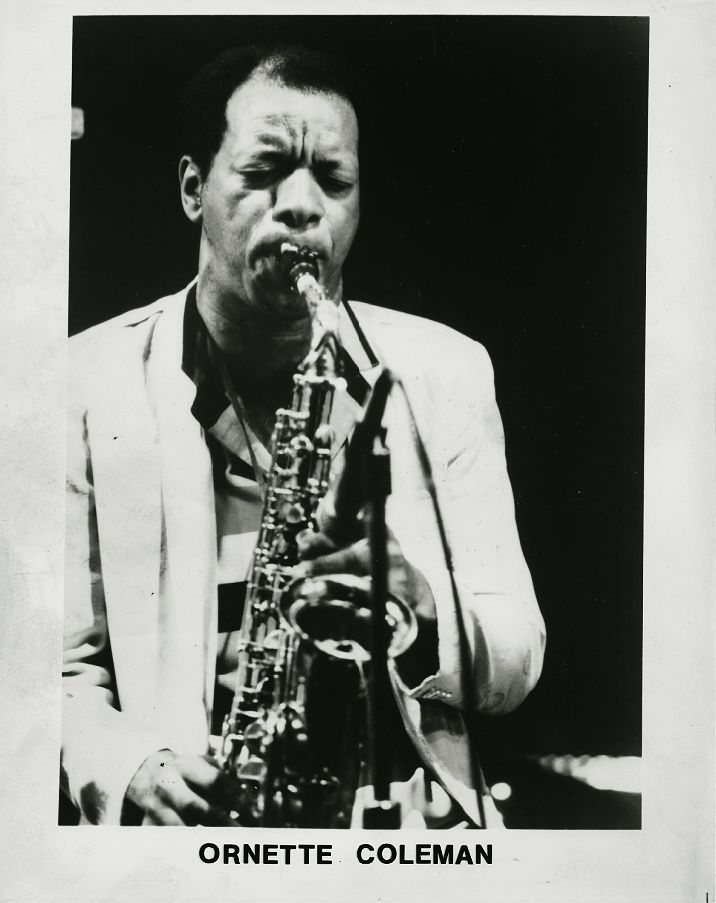

For an experimental jazz newbie like me, the music of Ornette Coleman has been a welcoming port of entry. Firstly, he has a cool name. Would my curiosity be as aroused by Terry Coleman? Reg Coleman? Probably not. Secondly, Ornette looks the part. He is the distinctive “man with the plastic horn”, a reference to the cream-coloured, acrylic plastic Grafton alto-sax he was pictured with in the early sixties.

Lastly, just look at the album titles: ‘The Shape Of Jazz To Come’, ‘This Is Our Music’, ‘Free Jazz’. These are more than just records, these are manifestos. 33rpm rallying cries I feel I can lend my voice to.

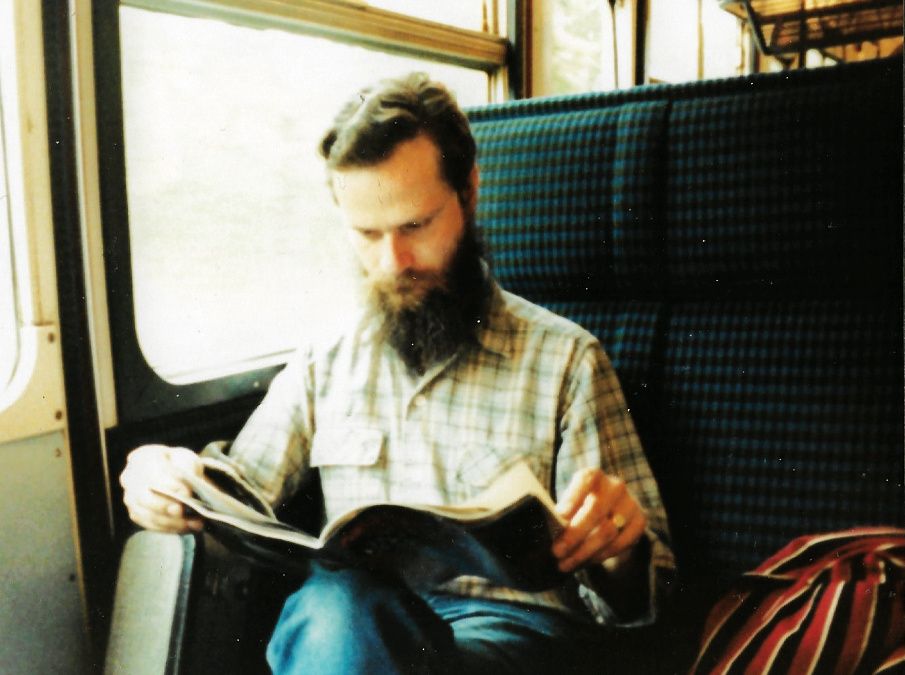

Charlie Collins, 1981. Photograph by Richard Barone.

So much for the look, what about the music? Charlie, endlessly patient and unfailingly helpful with my questions about jazz, has tried to explain Ornette Coleman’s theory of Harmolodics to me. Given that I am a self-taught drummer who cannot read a note of music, this is something of a challenge. Loosely, as I understand it, the players know where a piece will begin and end; but, within those loose parameters, it is pretty much a free-for-all. Traditional rules of harmony, melody, tone and time slip their moorings and the music is free to drift in any direction it wants.

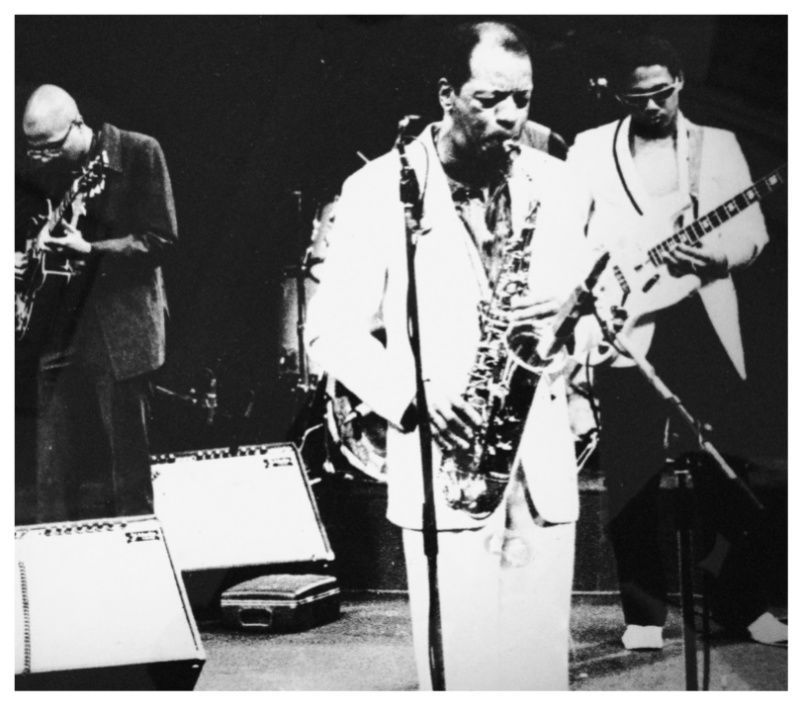

Prime Time are described as a double trio. What this looks like on the Crucible stage is a game of three-a-side. Two sets of drums, guitar and bass, all emphatically electric, mirror each other for kick-off – with Ornette stage centre as the referee. The soccer feel is added to by some ultra-chic football-shaped foldback monitors at the players’ feet.

Smartly dressed in a crisp white suit, Coleman looks every inch the innovator, both sonically and sartorially. A receding hairline, leaving an oxbow lake of forehead fuzz, is the only sign of ageing on a man just entering his sixth decade. Prime Time are togged out in a streetwise assortment of sharp threads, natty shirts and sports attire. They are, to a man, what Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones would describe as “cats”.

One of the two drummers, rat-a-tat-tatting from his foxhole of wood and metal, is Ornette Coleman’s son Denardo. Four years older than me, Denardo debuted on one of his Dad’s albums aged just ten years old. I have never seen anyone play the drums with the sense of unfettered glee and wild freedom that the younger Coleman brings to his assault. He’s like a child sat in a paddling pool, smacking the water, thrilled by the shock of the splash.

Aside from the grinning Denardo, the rest of the band do not put on much of a show. Ornette starts with a riff or melodic lick, neck muscles expanding and contracting like bellows, which the rest of the band set about deconstructing or embellishing as they see fit, each heading off on mazy solo explorations. Everyone is concentrating on their frets, one ear on what they’re playing, the other listening to the leader. An agitated dance of iron-filings drawn to an irresistible, ever-moving magnet. Prime Time have an album called ‘Dancing In Your Head’, and this is what they appear to be doing, cerebral bops of joy.

In the Crucible, no-one is dancing, though a few have made a lightning shimmy back out to the foyer, distressed by the rock band level of volume at which Prime Time operate. You could dance to this music, however, because while all the players seem to be going at it full pelt in their own silos, what emerges en masse is remarkably cohesive. There’s funk, there’s rock, even elements of calypso here and there. They play one I recognize, “Home Grown” off the ‘Body Meta’, an album I’ve borrowed from Charlie and taped. “Home Grown” has a jaunty, sing-song refrain, the kind you might hear on an ice-cream van, if said cornet(te)-purveyor was selling 99’s on the off-world colonies.

After just over an hour, Ornette, satisfied that Prime Time have completed another urgent, uninhibited exchange in what he calls ‘The Oldest Language’, leads his interpreters from the stage. The Crucible audience rises as one, sending them off to rapturous applause. Burning white-hot anthracite, the Coleman has delivered.

Thirsty for pints, we decide to skip the evening’s co-headliner, the easy-rolling township blues of pianist Dollar Brand, and head up West Street to The Beehive. We’re all still buzzing as we move on to The Limit. Charlie, who knows more about music than the rest of put together, reckons the last time he saw Ornette, at the Bracknell Jazz Festival in ’78, just shaded tonight’s gig. Even Paul, the most jazz-sceptic of us, has emerged unharmed from his first live Harmodolic experience.

The next day, on the bus on the way to work, I find a flyer in my jacket pocket for forthcoming plays at The Crucible. There’s a comedy by Alan Bleasdale called ‘No More Sitting On The Old School Bench’. No more sitting around for The Box either. Inspired by Ornette Coleman and Prime Time, we’ve got work to do.

_________________________________________________________________________

The Radio Hallam Jazz Festival, booked and supported by Steve Crocker and Bill McDonald at the station, ran until 1984. Moving away from The Crucible down to The Leadmill for the last two years.

Ornette Coleman, in a recording career that spanned the 1950s to the 1990s, released 25 studio albums and more than 20 live albums. Ornette died, aged 85, in 2015.

Thank you to Nigel Floyd, Damon Fairclough, Steve Crocker, Charlie Collins and Paul Widger.

The podcast edition of this blog can be found here.