“What time’s the soundcheck Paul?”

“Look, I don’t know. I don’t even know where the gig is, or even if there is a gig. All I know is that we’ve to be at Prague station at six to meet a bloke called Miloš and we take it from there. Alright?”

Oh dear. Just 24 hours into The Box’s biggest European tour to date and it’s already starting to get a bit tetchy in the Transit. This is the main event, headline shows in Vienna, Berlin and Amsterdam, with additional “due-to-public-demand” shows in The Netherlands, where there is a real danger of us becoming popular. But first there is the small matter of sneaking behind The Iron Curtain for a couple of days. And more importantly re-emerging unscathed in Austria with a full head count and the van and gear intact.

Paul’s right to be nervous. The plans for us to play two nights in Czechoslovakia - Prague tonight, Brno tomorrow - are, at best, optimistic. The tour itinerary from our live agent at All-Trade Booking simply instructs us to meet the mysterious Miloš at the main railway station, then let him take care of the rest. The negotiated fee for our night’s work, outlined in the money bit of the tour schedule, simply says, “handsome”.

Well, at least we’re in. Having spent last night in a youth hostel in Nuremberg, we crossed the border at Rozvadov. We’ve given packets of Marlboro Lights and cassette tapes by The Pointer Sisters and Manhattan Transfer to the border guards. Apparently they’re starved of American ciggies and Western pop music. Plus, of course, the compulsory, weighted exchange of Sterling to koruna. This has granted us access to the country on tourist visas, on the understanding that we’re just passing through en route to Austria, and won’t be working. No Siree Bob!

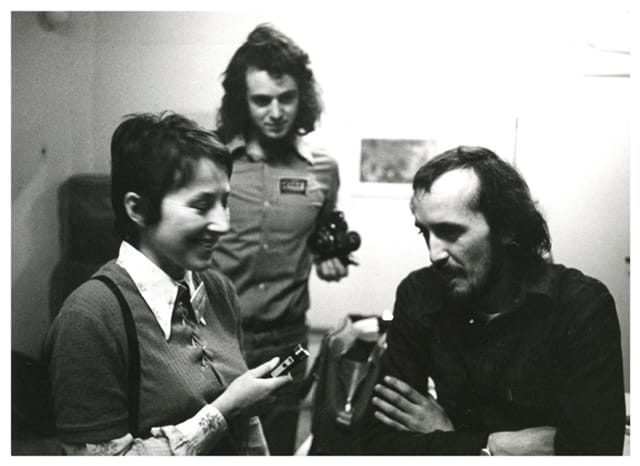

The main railway station in Prague turns out to be a rather beautiful Art Nouveau building, ebbing and flowing with Thursday evening commuters, all well insulated against the freezing weather. Given that we’ve no idea what Miloš looks like, it’s very much a case of six young English blokes (the band plus sound-engineer/driver Mark) standing around trying to look conspicuous (but not too conspicuous) until he finds us. Sure enough, after a few minutes a slightly-built guy with long hair, ‘tash and beard approaches us and says, in a wonderful, flutey-warbled accent: “I’m Miloš, welcome to Prague.” Here he is, our guide for the next 48 hours. Smiling and eagerly gesticulating, he looks like a seventies prog-rocker freshly sketched by Ralph Bakshi.

Very quickly, Miloš makes it clear that there is to be no gig for us tonight: “There are no boxes for The Box.” After a bit of head scratching, we work out that “boxes” are the PA system.

Apparently tomorrow night’s gig in Brno was more of a notion than a booking, so he’s going to try and source a PA for Friday instead. To make amends, a very apologetic Miloš offers to take us out to meet some local Czech rock musicians who have a prestigious gig in the city tonight.

We all pile into the van and head off for the town hall. This is the venue for an end-of-year prize giving ceremony for a local gymnastics club. It’s another handsome building, with a large sprung dance floor and an ornate, wraparound balcony, from where we watch the events of the evening unfold. Given the athletic nature of the gathering, it’s no surprise to see so many fit, good-looking girls and boys jiving and bopping to the music coming from the Pepa Pilař Classic Rock and Roll Band. As their name suggests, the band faithfully reproduces hits from the fifties: Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Buddy Holly standards. The sort of stuff I used to play in the school band five years ago.

During an interval, Miloš takes us backstage to meet the band. It’s slightly awkward as the local lads have no English and we don’t speak a word of Czech. Instead there is plenty of nodding, smiling and thumbs up encouragement before they return to the stage. It’s only then, when they kick into Jerry Lee’s ‘High School Confidential’, that I realise they’ve learned all these words phonetically. They don’t understand the literal meaning, but they know that they represent youth, sexuality and rebellion.

These songs shook the core of conservative America twenty-five years ago, and it’s a pleasure to hear their sweetly subversive, authority questioning, heavily-accented lyrics ring out tonight. It doesn’t matter if your accent is Sheff or Slovak, Awopbopaloobop alopbamboom is a universal language.

We’re only an hour from Pilsen, so the beer here is terrific and very, very cheap. We get talking to some of the local kids who speak English:

“We love Margaret Thatcher because she stands up to the Russians!”

“No, you don’t understand, she is ruining our country.”

“Sorry, but you don’t understand. You are free to publicly criticise her, we can’t do that here.”

Pepa Pilař and his band rave on and rip it up, medals and trophies are awarded, recipients give short speeches which, I assume, thank parents and coaches. More beer is drunk, until it’s time to leave. But where are we going? Miloš has arranged for us to crash at a friend’s house. Milan “Mejla” Hlavsa is a co-founder of The Plastic People of the Universe rock band, who since formation in the late sixties have regularly defied the Czech Communist regime. Milan also owns the only authentic Fender Jazz Bass guitar in the country.

A white Ford Transit from Beauchief Van Hire is something of a rarity late at night in the suburbs of Prague, so - to no-one's great surprise - we get pulled over by a local Police patrol. Like the border guards earlier, the cops are civil. Flash lights are waved around, passports and visas are checked. Miloš, smooth as molasses, does all the talking and we are soon on our way again.

An invitation to the kitchen for a simple, mid-morning breakfast - black coffee, bread, jam - tempts me to leave the warmth of a sleeping bag on a couch. Our genial hosts tell us there was a knock on the door at 8am, a couple of representatives of the phone company checking a fault on the line. The “phone company” here is a local euphemism for the StB, or secret police. They’re putting a bug on the line as there are Westerners at the address. This intrusion is accepted with great calm and matter-of-fact-ness, and I wonder if this isn’t the first time that such a visit has been made.

Having entertained us with some local rock’n’roll last night, today Miloš says he is going to show us some Czech art. Rather than heading back into the city, he directs us to a small village called Středokluky, out near the airport.

It’s a cold bright blue December day when we tumble out of the van. The first thing I see is an old woman kneeling with a zinc washboard, hand wringing some clothes and bedding in a fast-flowing stream at the side of the road.

Her fingers are a blue-ish white colour, and I shiver internally as I try to imagine how cold she must be. She looks directly at me and I think about taking a picture, then remember that Sex Pistols’ lyric about “a cheap holiday in other people’s misery” and decide against it.

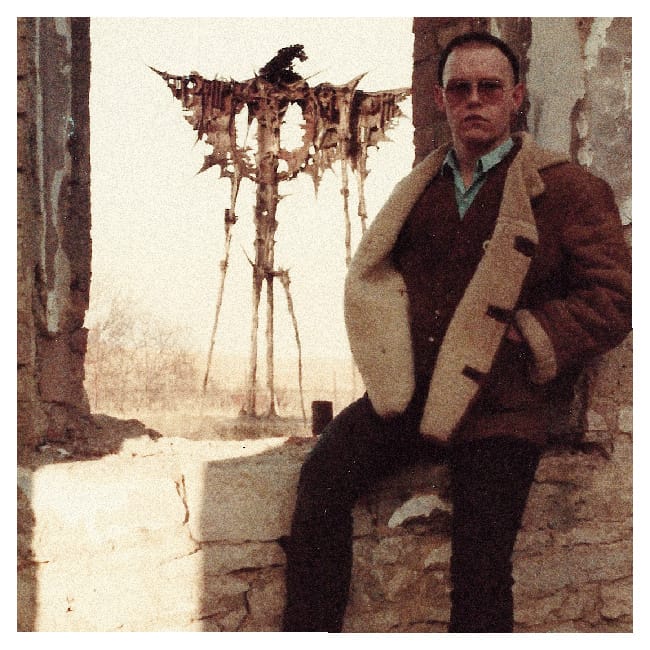

We have come to visit the studio of sculpture artist Aleš Veselý, who has converted an old mill he owns into a work base. Aleš also plays in an alternative music band called Frog’s Slime. It’s becoming clear to us that Miloš pretty much knows everyone involved in what might be described as the Czech counter-culture. Bohemian by birth, bohemian by nature.

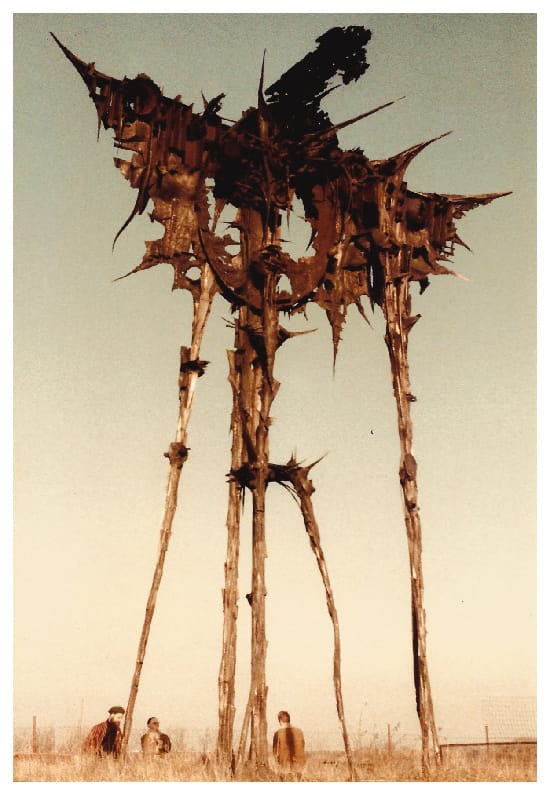

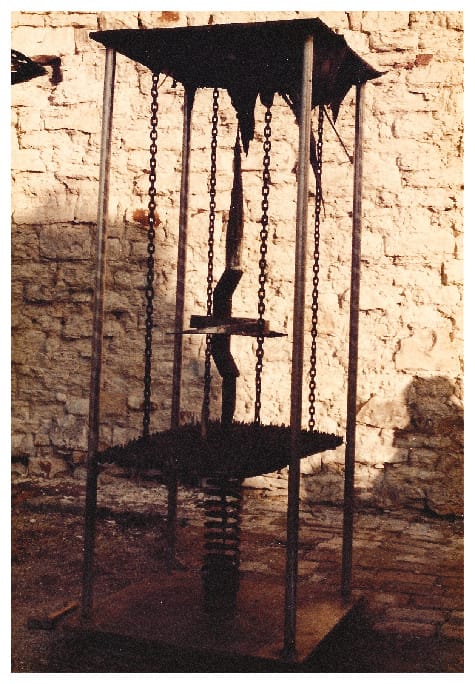

Veselý’s sprawling site is dominated by a magnificent, towering 25-foot-tall metal work called ‘Kaddish’, which he has brought home from Ostrava, where it faced demolition. A bewildering fusion of Ted Hughes’ ‘Iron Giant’ and H.R. Giger-style spread eagle wings, this metal monster appears to hover over the surrounding fields.

The artist works with metal, wood, stone and found objects, using an acetylene torch instead of a paint brush. And while no other pieces in his yard can match the sheer size and awe of ‘Kaddish’, he’s not a man who goes in for anything less than larger than life. Giant stone hands, bizarre sculptures that are part musical instrument and part instrument of torture. He allows the weather to add the final elemental coat, accepting that oxidation is part of the process.

The many clanging metal chains and taut steel surfaces appeal to our inner-Neubaten instincts, so I nip back to the van to gather some drum sticks. Armed with these, we beat out some rattling industrial rhythms, a spontaneous session in tribute to our favourite Berliners.

Aleš passes around some mulled wine, which also helps to take the winter chill away. Soon it’s time to head back into Prague, and Miloš leaves us while we do a bit of sight-seeing. We’ve done high-concept sculpture already today, so after the obligatory wander across the Charles Bridge, we settle into a slightly fusty, dusty bar with old oak tables, just off Wenceslas Square, for a few more dirt cheap pints.

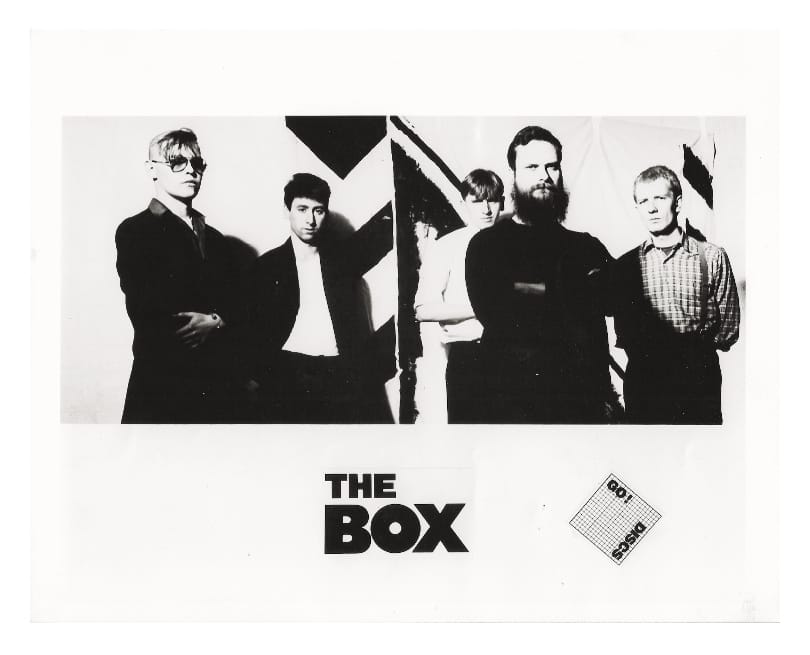

The Box’s debut album on Go! Discs has been critically well-received, and label boss Andy has managed to secure a licence deal with Dutch label Roadrunner Records. He wants us to make a second album in the new year, which we are thrilled about. He’s also just released the debut album by a guy called Billy Bragg, just a working class bloke from Essex and his electric guitar, which seems to be doing well for the label.

The mood is much improved after yesterday’s tension. We might be the best part of a thousand miles away from home, but the friendly welcome we’ve received is genuinely appreciated. And we’re still marvelling at how inexpensive everything is.

“You could live like a king here,”, I suggest, as another round of beers materialises. “Yes, Rog,” smiles Charlie, “a good king.” Meanwhile, Miloš returns with encouraging news. He has found a PA for us to use tonight, so the gig is on.

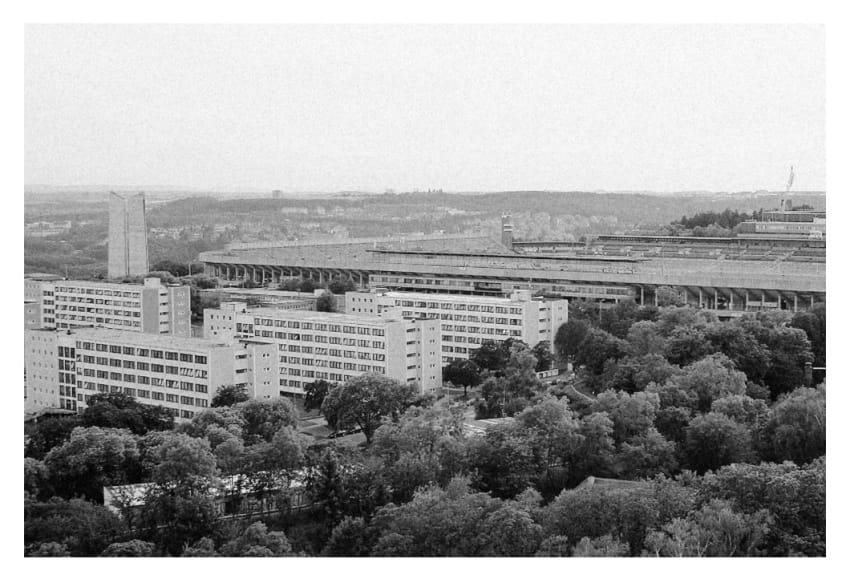

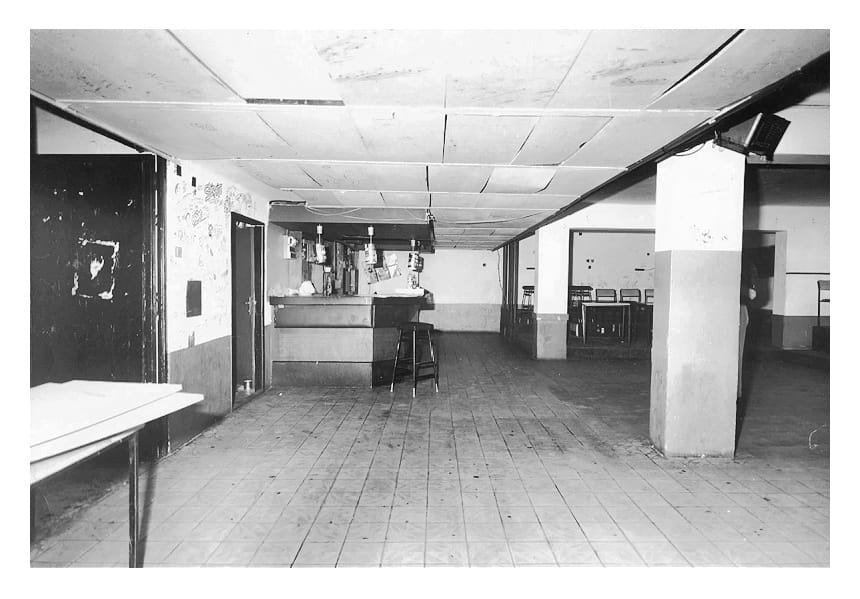

Miloš having directed us away from the old town, we cross the Vltava river heading west, climbing away towards the Strahov district, the location of the Czech Technical University. Soon after, we are greeted by ten identical dormitory blocks, white brutalist shoe boxes glowing with the light coming from hundreds of windows, as thousands of Czech students make plans for their Friday night fun. Having located the right block, we unload the gear into a sparsely decorated basement room.

Much to our surprise, there are about a hundred people there already, sitting around on bits of old furniture or stretched out on the floor, waiting for us. Miloš explains that since tonight’s gig is unofficial, the news about a band from the UK playing has been passed along person-to-person. No ads, no posters, no flyers, just old-fashioned word-of-mouth. It’s flattering that so many have ventured out to see a band that most of them have probably never heard of, so we waste no time in setting up at one end of the room where the PA is situated.

We haven’t played in front of an audience since some Dutch shows in September, and I’m worried that we might be a bit rusty in front of a crowd. Four clicks on my sticks and we’re off. The start of our pressing interrogation of sound and the space around it. The nods and the glances between us, the blinks and winks, as we search for a kind of musical neutral buoyancy, where we become immersed in the current that pushes our wave of noise towards the audience. No wear and tear here, we sound fresh. A couple more look-sees and we bring it home on the button.

Silence. Puzzlement. The only sound is the buzz from the amps.

Tough crowd.

No matter, push on. Here we go, maybe a little less staccato, lean towards the legato? Warming up, blood pumping now. Take a second to admire a long lunar note from Paul, a seamless glissando from Charlie, Goodness me, I’m lucky to play with these lads. Uh, watch out! These songs don’t hang about, here's the ending. Nailed it.

Nothing. Or, in Czech, nic.

Blimey. I mean, it’s not as if we had low expectations for this gig, because until a few hours ago we had no expectations at all. Is it something Pete said? “Hello Prague, we’re The Box.” shouldn’t cause offence. Is the PA working? More inter-band glances, longer now; mumble and shrug into the third song. It ends, and we’re getting crushed by the hush.

Sensing our discomfort, Miloš scampers across the floor to us:

“Guys, don’t worry! They love you. But if they clap you, that makes it a performance, which is illegal, and they would be breaking the law. So if they just watch you in silence, that means you are just rehearsing, which is okay. No-one will be in danger of arrest!”

Okay then. The first feeling is a sense of relief, they don’t hate us, swiftly followed by sadness. I momentarily reflect on the absurdity of the situation and the extraordinary lengths these music fans have to go to enjoy something we take for granted. We relax a bit, and the rest of the gig takes on the air of a performance art installation, a rock band thrashing away to a mute, apparently impassive audience, in an airless basement. This peculiar concert is extended further when we play half the set again for an anguished latecomer. Definitely one of the strangest gigs I’ve ever been a part of.

Afterwards, they pass a cap around for us. By local standards, it is not an insubstantial sum of money. We are thrilled and thankful for such generosity. Miloš suggests we go out to celebrate and offers to take us to the best restaurant in Prague.

On arrival at the Olympia, we sit down and order what was always described in the Beano as “a slap-up meal”. Miloš is an interesting host; he’s been a freelance journalist, Funerary art expert and founder of the rock and jazz centre in the city.

Through one platform or another, he’s been actively opposing the occupying communists since 1969. We’re in safe hands, he’s arranged or co-arranged Prague gigs for This Heat, Skeleton Crew and Nico. Many toasts are proposed, glasses are raised and addresses are exchanged. Hearty food, red wine and slivovitz combine to give me a warm glow inside, one that I haven’t felt since I stopped having Ready Brek for breakfast.

We say our farewells on a cold, bright Saturday morning, and driver Mark points the van towards Vienna, a journey of just over 200 miles. Paul, who is in charge of the kitty, counts the well-fingered koruna banknotes. By his calculations, last night’s meal and wine for seven came to about thirty quid. This presents something of a problem, as, given the mandatory money exchange when we entered the country a couple of days ago, we’re supposed to be leaving with less local lolly than we had when we came in.

Charlie’s idea is to shove the bundle of surplus cash through a random letterbox on the outskirts of Brno, an anonymous early Christmas gift from some kind of Moravian Robin Hood. This is knocked back, because, given the level of paranoia ordinary folks seem to live with here, there’s every chance that the offering might be met with fear and suspicion by the surprised recipient. We’re still umming and ahhing about the cash when we reach the Austrian border.

Paul the diplomat goes off to speak to the Czech security guards.

He returns ten minutes later, smiling. “I told them I won it in a card game in Prague. They were fine about that, but we have to spend it in the gift shop.”

Said shop is a sorry looking concrete shed by the side of the road. Tragically, there is no alcohol on sale. We end up spending most of the cash on slabs of chocolate and football pennants. I feel well enough equipped to be confident that I could walk to any halfway line in central Europe before kick-off with the right club souvenir ready to exchange.

Satisfied that we’ve spent their currency in their country, the guards happily wave us through. It’s been an unexpected pleasure to spend some time in Prague. We came with few presumptions and have been warmly welcomed and inspired by the people we encountered. That said, it's been five days since anyone in the van saw a bath or a shower. It’s getting funky in here and not in the James Brown way. A hotel in Vienna awaits the grimy herd.

On entering Austria, the border police stop us and order us to empty the entire van. For over an hour, they check every packet of guitar strings, every amp lead and every reed in Charlie’s sax cases.

Welcome to the West.

Huge thanks to Miloš Čuřík for his invaluable help in recalling some location details which were missing from my memory.

Thanks also to Paul Widger.

Edited by Nigel Floyd.

Remembering Milan “Mejla” Hlavsa, who died in 2001, aged 49. Also Aleš Veselý who died in 2015, aged 80.

An edited version of the industrial field recording that The Box made at Aleš Veselý's work space can be found on Bandcamp.

Link here - https://csindustrial1982-2010.bandcamp.com/album/2-12-83-bohemia