Sunday morning. The Free Jazz Express, bound for London Saint Pancras, flams and rolls over the points as it leaves Sheffield Midland Station. I’m on board with band-mate Charlie, Charlie’s pal and fellow saxophonist, Derek Saw, and John Capes, owner of Rare & Racy, Sheffield’s finest music outlet for those with off-beat tastes. Here we are, amidst the psst of cans of Guinness being sprung, salty fingers rummaging in crisp packets and the rustle of Sunday papers; three jazz messengers and one jazz passenger.

In my musical education, I am happy to play Kwai Chang Caine to Charlie’s Master Kan. A few years older than me, and way more worldly, he’s the only person I know who has seen both Jimi Hendrix and Aretha Franklin live. He remembers when MOR balladeers Chicago were blowing minds with free-form guitar wig-outs as Chicago Transit Authority. He’s the only man I know who can terrify the bejesus out of his sax and then, with nary the lick of his lips, slip into the glorious riff from ‘Move On Up’. In the eighteen months we were in DVA together, he’s taken me under his wing, and shielded me from some of the more bacchanalian excesses the band had a well-deserved reputation for.

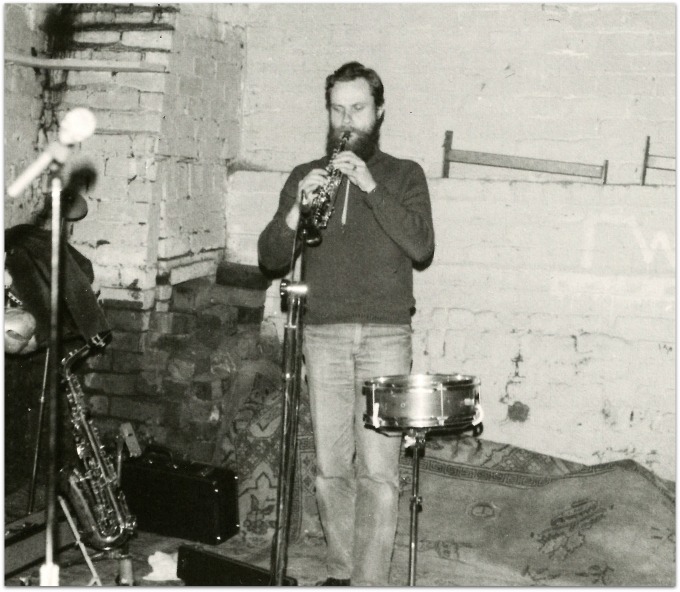

Charlie Collins, DVA rehearsal room, West Street, Sheffield, circa 1980.

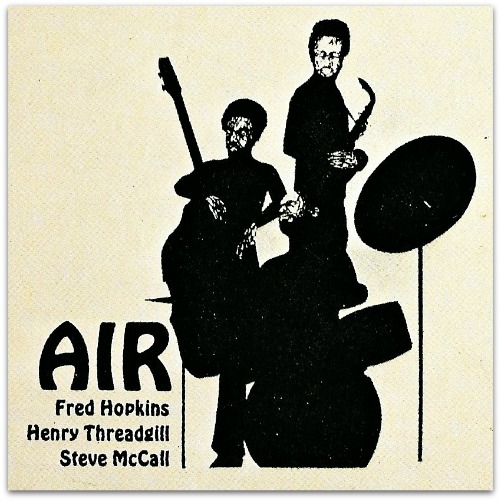

The four of us are off to see Air, a free-jazz trio from Chicago, who are on a rare trip to the UK. I’ve learnt from Charlie that the windy city has played a critical role in the development of jazz, being the base for the formation, in 1965, of The Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, or AACM for short. One of the founders of the AACM, Steve McCall, is the man behind the traps in Air.

As well as seeing the gig, Charlie and I have some musical business of our own to attend to. We are staying in Pimlico with Rod Pearce; Rod being the owner of Fetish Records, who just released the second DVA album – ‘Thirst’ – and who has plans to release a live recording of the band’s performance at the Fetish Night Out at London’s Lyceum Theatre back in January. Charlie is travelling with two of his precious saxes, as we are to head down to Jacob’s recording studio in Farnham tomorrow, to review the live tapes. Charlie will also guest on a couple of tracks for US new-wave sprites The Bongos, who are also signed to Fetish.

This is to be my first bona fide jazz gig, and I have Charlie to thank for this. He lives in a comfy semi-detached house up at Crosspool. His enthusiasm for music is infectious: “Have you heard ‘It’s A Trip’ by The Last Poets? It’s the funkiest track EVER!” He puts it on the stereo, and it is indeed the funkiest thing I have ever heard.

So many records to discover and treasure: “Full Force” by the Art Ensemble of Chicago, “Body Meta” by Ornette Coleman, “Lenox Avenue Breakdown” by Arthur Blythe. Albums by Anthony Braxton, Julius Hemphill, Marion Brown, Don Cherry and David Murray; from time-to-time Charlie and I will play Murray’s elegant ‘Flowers For Albert’ together in the rehearsal room, me splashing around in the shallow-end, Charlie going off the top board as he plunges into this beautiful, malleable melody.

Hungry to learn more, I cram in more jazz from the record library on Surrey Street. Home taping might be killing music, but it’s giving me the kiss of life. Personalities like Rahsaan Roland Kirk, who blows two horns at once, and Venusian immigrant Sun Ra. Music by Babatunde Olatunji, Cecil Taylor, Miles Davis and the towering tenor sax of John Coltrane. Val Wilmer’s “As Serious As Your Life”, the definitive treatise on free jazz, becomes my bible, as I add Archie Shepps’ soulful “A Sea Of Faces” to my collection, second-hand from Rare & Racy.

Rebuilt two years ago, the plush environs of the Lyric Theatre couldn’t be more of a contrast with the last venue I visited in Hammersmith, the tatty Clarendon pub marooned on the A4 roundabout just up the road. Taking a break from Ibsen and Hare, the theatre bar atmosphere is blokey, beardy and bohemian. As much as I tell myself I’ve got broad, inclusive tastes in music, this will be my first concert watching black musicians. It must say something about my gig-going history that the only black guy I’ve seen onstage in the past three years is the Maori bass player in Be Bop Deluxe. Say Be Bop Deluxe to these guys and they’ll probably think of a jam session with Charlie Parker. Beyond what I’ve listened to on record, my exposure to live improvised music has been confined to the rock end of the spectrum: the ground-zero impact of Throbbing Gristle, the doleful De Tian, the impish freakery of Naked Pygmy Voles and a vituperative blast of Ted Milton’s Blurt at The Marples in a blizzard last month.

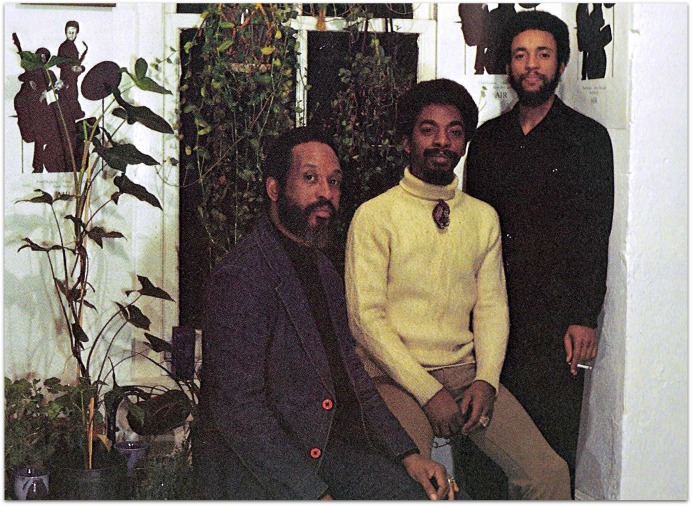

AIR - (L-R) Steve McCall, Fred Hopkins, Henry Threadgill.

Air – AACM founder McCall on drums, plus double bass player Fred Hopkins and saxophonist Henry Threadgill (why do have all these jazz guys have such cool names?) – take to the stage. The Lyric is quieter than a class of meditating librarians. There will be none of the joshing chatter that soundtracks my usual gig experience, the mood is one of hushed approbation. It’s appropriate, then, that Air start very softly, with minimal amplification. The saxophonist opts instead to play flute, as the drummer shakes and dings various exotic looking pieces of percussion, while the bassist taps and knocks at the belly and bout. Painting with sound, they conjure up a scene that could be a sleepy Thai peasant village; all that’s missing is a crowing rooster.

From this bucolic beginning, Henry Threadgill clips on his saxophone, and starts an audacious game of musical snakes and ladders. Each member of the trio takes turns to roll the dice and make bold steps forward, come what may. Quicksilver flurried runs up the steps of the tenor sax keys are countermanded by Fred Hopkins’ glissando dive-bombing down the neck of his bass. Behind him, Steve McCall rattles the skins and urges his compadres to roll again, roll again. I’m fascinated by their control, in particular by the dramatic way they switch from surge to hush without so much as a nod; it appears to be almost telepathic. Listening to a rock bands playing through a big PA can feel like the music is being pushed at you in one big sonic block, even the quieter songs. I’m learning that controlled volume, each player having the skill to rise and fall on cue, can be more impactful and dynamic; you lean in for the soft bits, only for the thunder to rock you back in your seat.

I’m fascinated by Fred Hopkins, who’s the best bass player I’ve ever seen. His instrument is bigger than him. Does it support Fred, or does he support it? This mutual dependency runs the spectrum from swaying slow dances, together in his embrace, to gentle, aching bowing and then again to treating it mean, his fingers plucking lasciviously, beating around the f-hole with sticks and mallets. The intimacy appears to create a singular beast: part-man, part-maple. As Henry Threadgill wrings another piercing solo from his instrument, there are unconfirmed reports of minke whales swimming up the Thames to Hammersmith Bridge to duet with his celestial sound.

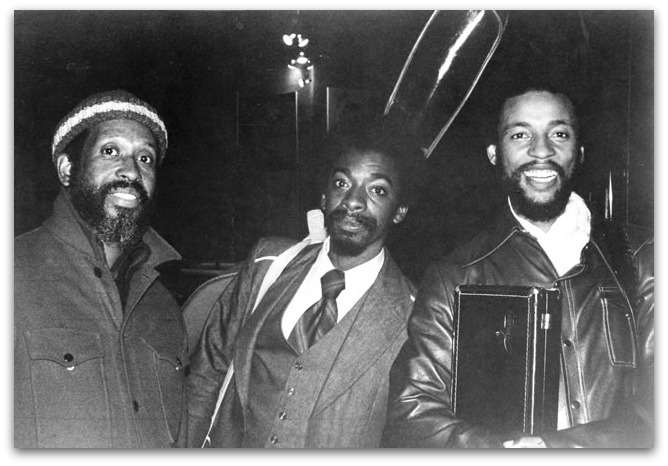

AIR - (L-R) McCall, Hopkins, Threadgill.

Later, in The Swan, we reflect over what has been, for me, a revelatory experience. Charlie tells me Air have a signature piece called ‘Keep Right On Playing Thru’ The Mirror Over The Water’, which makes perfect sense. A rich mixture of elements experimenting with reflections of light and sound.

Charlie and I catch the last tube back to Rod’s cosy garret. Rod is sanguine about the DVA split. ‘4 Hours’ has just been released as a single from the album, and he’s still keen to release a live album. Charlie tells me that Rough Trade heard an advance copy of the album last year and offered Rod £5,000 for the rights, but he turned them down. I wonder if he regrets that now?

With Monday comes Richard Barone, bleary-eyed Bongo-in-chief, just off the red-eye from New York. Off we troop to Waterloo, to catch the train to Farnham, where Ken Thomas is waiting for us at Jacob’s Studios. No doubt inspired by last night’s sorcery, Charlie tears off a ferocious sax solo which runs the gamut from gut-wrenching, low-end rumbling to kettle boiling, bat-bothering high frequencies. On another song, Ken simply close-mics Charlie’s fingers as he makes his instrument’s key pads into a unique percussion instrument. I am a little in awe of my band mates’ inventions.

There’s a full moon over Farnham as we leave Richard and Ken to get on with The Bongos album. Back at Rod’s flat for one final night on his fold-out camp beds, we watch ‘McCabe & Mrs. Miller’ on VHS. For the first time in my life, the music of Leonard Cohen – sad, moribund “Laughing Len” as we called him at school – finally makes sense to me. Another night, another little epiphany.

Steve McCall left AIR in 1982. He died, aged 56, in 1989. Fred Hopkins and Henry Threadgill continued to record as New Air until 1987. Hopkins died in Chicago in 1999, aged 52.

Henry Threadgill, who served with the US Army in Vietnam, has appeared on over sixty albums. In 2016, he received the Pulitzer Prize for Music.

Spotify playlist here.

For more pictures etc check out https://mylifeinthemoshofghosts.tumblr.com/